|

|

. |

| |

|

|

| |

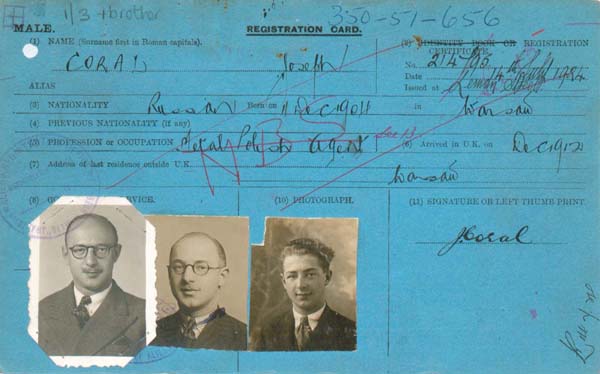

Joe Coral (born Joseph

Kagarlitsky)

b. in Warsaw, Poland

11 December 1904

d. 16 December 1996, University College Hospital, London

(lung cancer)

Joe Coral (then

Joseph Kagarlitsky) was born in into a Jewish family in Warsaw, Poland in 1904.

His father, Abraham Kagarlitsky, died when he was at an early age and his

mother, Jessica, joined a wave of migrants in 1912 from Eastern Europe who were

seeking a better life in the United Kingdom.

The family took on the

surname Coral and Joseph became Joe to make it easier to get a job, of which he

had many after leaving school at the age of 14. Having a flair for mathematics

Joe took a clerk's position in a lamp-making firm which gave him the

connections to meet bookmakers and become a 'runner' (someone who takes bets on

behalf of a bookmaker - illegal since 1853).

Joe was sacked from the

lamp-maker's workshop for, in Coral's words, ‘concentrating on the wrong

ledger’. From there he went to work at a small London advertising agency

which gave him enough time off begin taking bets in a billiards club in Stoke

Newington during the General Strike of 1926. In 1927 he left advertising to set

up his own pitches at the Harringay and White City greyhound racing tracks. The

introduction of the electric hare from the United States of America in 1926

assisted Coral's career as it created a legal context for trackside betting in

London.

Joe Coral and his brother had failed to register as 'aliens'

resident in the UK until 1924 and were fined £20 each at Thames

Magistrates Court. It was the beginning of a long running feud that would see

Joe on the wrong side of the law until 1952.

Like many bookies of the

time, Joe Coral ran both a legal and an illegal trade. The legitimate side of

the business was greyhound racing and credit betting with cheques, where no

ready money changed hands, but the most lucrative wing of his business was

street betting. He made strong efforts to develope a local network of agents to

collect bets on his behalf in pubs, shops and back alleyways. By 1930 he

employed between seventy and eighty agents who collected ready-money bets for

him. By that year he had also taken over the pitches of Bill Chandler, a

popular Hoxton bookie, who was unable to compete with Coral.

Joe Coral's

success as a bookie got the attention of Charles Sabini, commonly known as

Darby Sabini, a gang leader of mixed Italian and English parentage. Darby

Sabini was head of the Sabinis and 'king of the racecourse gangs' that

dominated the London underworld and racecourses throughout the south of England

for much of the early twentieth century. Sabini had extensive police and

political connections including judges, politicians and police officials.

Sabini's power rested on an alliance of Italians and Jewish bookmakers but Joe

Coral managed to defend himself from the racecourse protection rackets

operating against bookmakers. It was a dangerous time for Joe but he was

relieved of the pressure when Sabini moved to Brighton to run the same

operations there. Sabini was later immortalized as the gangster Colleoni in

Graham Greene's Brighton Rock.

Joe Coral was one of the largest regional

bookmakers in England by 1939. War interrupted the betting business, owing to

the huge reductions in the racing calendar, but Coral was still busy. He opened

a credit betting office in Stoke Newington in 1941, and moved the office to

London's West End four years later. After the war, moreover, Coral was one of a

number of bookmakers who advertised betting by post in the major sporting

newspapers such as the Sporting Life and the Sporting Chronicle.

‘Sporting’ newspapers were really betting newspapers. Betting

by post was legal because no cash changed hands, only cheques or postal orders.

The illegal business continued to thrive, however, but the 1950s witnessed a

thawing of official attitudes to betting and gambling. During an era of full

employment and affluence the idea that the working classes would gamble

themselves into poverty was misplaced. The police also took the opportunity to

argue to the royal commission on betting, lotteries and gaming of 1949–51

that the law was unworkable, and that illegal betting was an open secret which

was impossible to stop. This change of mind led to the Betting and Gaming Act

of 1960, which finally legalized off-course cash betting, and introduced the

licensed betting office to the high streets and back streets of England and

Wales.

Joe continued his battle with the authorities over his status as

a citizen. The Aliens Restriction (Amendment) Act 1919 was the legislation that

gave to the government the power to require such individuals to register with

the police and to pay a registration fee. In return the individual received a

police certificate of registration. The cards had to be updated every three

years and were known as continuation cards. Joe's card for 1932 - 1935 shows

him being fined £40 for failing to notify the police of change of address

in 1932. Coral was then cautioned by letter in 1935 for failing to report his

marriage which took place in 1932. The last extract from Joe Coral's cards

shows that in 1943 he was cautioned again by letter for failing to notify an

intended change of address. The details on the cards continue until his

application for naturalisation in 1952. The initial Home Office reaction,

according to a file released at the National Archives, was to refuse. But

senior figures decided that the driving offences and unproven suspicions were

not sufficient grounds. One official commented: "For a bookmaker in Stoke

Newington he is not a bad sort of fellow."

|

| |

|

| |

Joe

Coral, along with other bookmakers such as William

Hill, were not keen about legalization. A requirement of the 1960 act was

that any new betting office needed to show ‘unstimulated demand’

before being granted a licence. One way was to convert existing business

premises to a licensed betting office. Coral paid to have the sweetshop of one

of his agents turned into a betting shop. The most efficient way, however, to

negotiate the new law was to buy up other offices, and by 1962 Coral had

twenty-three shops. Subsequently during the 1960s the corporate structure of

bookmaking became more fully fledged, and bookmaking firms became public

companies, operating on a legal and commercial basis. Corals became a public

limited company in 1963, and diversified into casinos, bingo halls, and hotels.

The firm was bought, in 1970, by the brewing, hotels, and entertainments group

Bass. The motives for the take-over were clear: Corals' annual profits were

£1.5 million in that year. He remained president of the bookmaking firm

and a major company director.

By the mid-1970s expansion had produced

650 Corals bookmakers' shops, and by the end of the decade Corals was one of

the ‘big four’ bookmaking firms. It retained that status into the

1990s. In 1992 Corals entered into an arrangement with the tote, the pool

betting system based at the racecourses, whereby pool bets could be placed at

Corals outlets.

Coral had married his wife, Dorothy Helen, in 1932. They

brought up three sons, two of whom, Bernard and Nicholas, pursued careers in

the family business from the early 1950s. Joe Coral died in University College

Hospital, Camden, London, on 16 December 1996 from lung cancer, having suffered

from dementia for some years. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

. |

|

|